By Esteban Pérez Caldentey (guest blogger)*

Over the past three decades Latin America and the Caribbean have experienced lower long-run growth in relation to other regions. The available evidence indicates that Latin America and the Caribbean had the highest levels of GDP per capita growth in the 1970’s decade in relation to other regions, with the exception of East Asia and the Pacific. Thereafter, the region has registered one of the lowest rates of growth of GDP per capita in relation to other developing regions for most of the periods under consideration (1981-1990; 1991-2000; 2001-2009, 2001-2011). Moreover the growth differential between Latin America and the Caribbean and other regions such as the case of East Asia and the Pacific has widened over time.

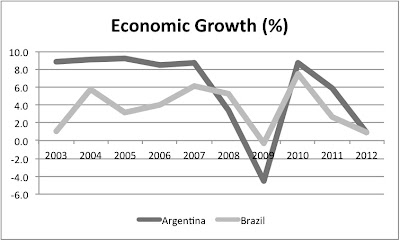

The most recent period of expansion (2003-2007) does not constitute an exception to this observed trend. During this time Latin America and the Caribbean experienced the highest average rate of growth in over three decades. The regional average per capita growth rate reached 3.7% surpassing not only that of the 1980’s lost decade and that registered during the free market structural reform era (1991-2000) (1.4%) but also that of the 1970’s (3.2%).

However, on a comparative basis, Latin America and the Caribbean’s performance was by no means an exceptional one. In fact the regional rate of growth remained significantly below those of East Asia and Pacific (9.3%), Europe and Central Asia (7.4%) and South Asia (6.6%).

In a recent paper (

Weak expansions: A distinctive feature of the business cycle in Latin American and the Caribbean) we (Esteban Pérez Caldentey, Daniel Titelman and Pablo Carvallo) argue that part of the explanation lies in the specific features of the Latin American and Caribbean cycle. In spite of the fact that cycle fluctuations are traditionally associated with a short-period context, these can also impinge on long-run growth by their effects on investment and productivity, among other variables.

According to our analysis which uses two standard cycle methodologies (Classical and Deviation Cycle) and a comprehensive sample of 83 countries worldwide including all developing regions, we show that the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) cycle exhibits two distinctive features.

The first and most important one, is that Latin America and the Caribbean register weaker expansions, both in terms of duration and intensity, than those of other regions and in particular than those of the East Asian and Pacific region.

The most recent expansion (2003-2007,) which is by far one of the most intense in the history of the region, does not alter this conclusion in the least. This expansion episode falls short both in terms of duration and amplitude when compared to the last expansion episode of other regions and in particular to that of East Asia and the Pacific (26.5 quarters and 29.8% for Latin America and the Caribbean and 40 quarters and 53.9% for East Asia and the Pacific respectively)

A second distinctive feature is that Latin America and the Caribbean’s contractions conform in terms of duration and amplitude to those of the rest of the world.

Weaker expansions and convergent contractions imply, as a result, that the complete cycle of expansions and contractions tends to be shorter and with a smaller amplitude, for Latin America and the Caribbean relative to other regions of the world.

The findings presented in this paper open important avenues to further explore and analyze the short and long-term performance of Latin America and Caribbean economies.

First cycle analysis should increase its focus on the nature and behavior of expansions. Sustaining evidence is provided by the fact that contractions tend to be somewhat homogeneous across regions in terms of duration and amplitude. However, this is not the case of expansions. Expansions are heterogeneous in terms of duration and amplitude. Improving our understanding of the differences in the expansionary dynamics of countries and regions, can further our understanding of the differences in their rates of growth and levels of development, including those of Latin America and the Caribbean.

Second, as it is well established, the management of the cycle affects the short-run fluctuations of economic activity and hence volatility. But in addition, it is not trend neutral. Hence, the effects of aggregate demand management policies may be more persistent over time and less transitory than currently thought. This provides a justification to reconsider the usefulness of stabilization policies and their effects, from a short and long run view, including their potential trade-offs, and to re-think how to articulate and coordinate what are currently called demand side with supply side policies.

* Economic Affairs Officer at the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Santiago, Chile. The opinions here expressed are the author's own and not necessarily those of the institution with which he is affiliated.