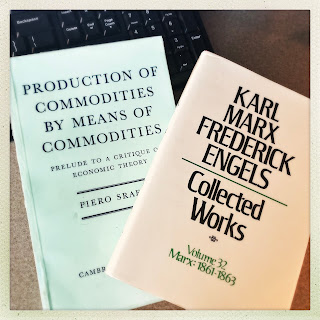

A few years back in Colombia, we discussed with a group of students about a possible reading group of Sraffa's Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities (PCMC). After the pandemic I thought that the experience with Zoom perhaps created the conditions for that. But I also have a concern expressed here several times (see here and here) about the lack of understanding of the theory of value and distribution and its importance for policy analysis, and not just among mainstream economists.

At any rate, I decided to give 6 Lectures online (that I will record and post eventually) on the theory of value and distribution. It will cover from before Adam Smith to modern times. Authors discussed will include Smith, Ricardo, Marx, Marginalist ones (Clark, Marshall, Wicksell), Sraffa, Samuelson and Garegnani. The Capital Debates, and the Modern Intertemporal Marginalist approach will also be discussed.

This will not be an advanced seminar for graduate students that already know quite a bit about these topics, but for advanced undergraduates and perhaps masters students in mainstream programs (or heterodox ones that do not cover these issues), which have limited understanding of the theory of value and distribution. Readings will include the relevant chapters or papers by the main authors in the original (not a textbook, even though I will suggest a few; and yes, some chapters of PCMC too). I intend to have a discussion session after each lecture (which will not be posted online). If you are interested email me with a brief explanation of your background and why this would be relevant for you to mv587062@gmail.com.

Dates, Zoom links and a syllabus will be provided for those that participate (yes, it is free).