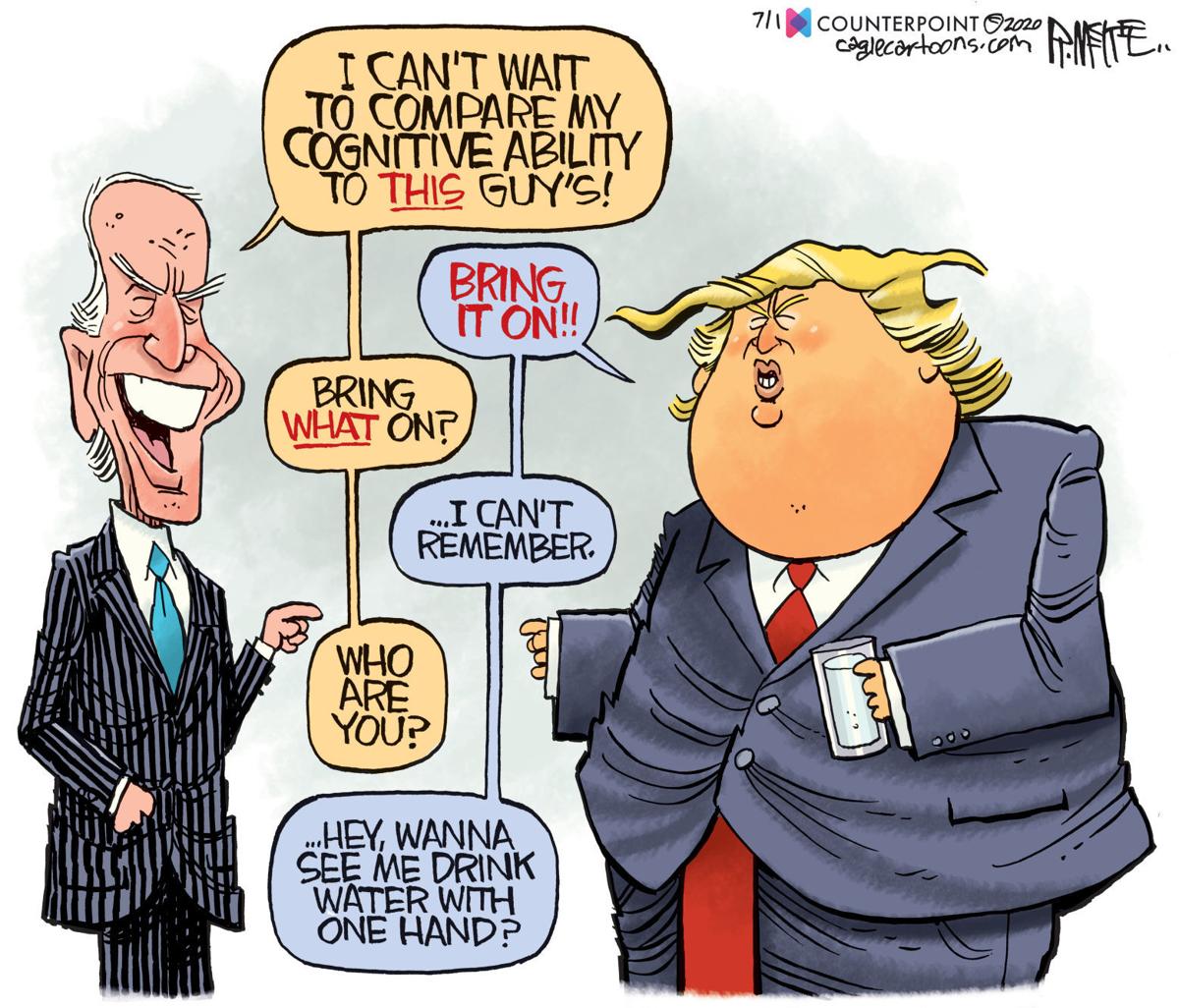

The debate between Biden and Trump is on everybody's mind. And for good reason, the future of the global economy, and the well being of the planet are always at stake in American elections. I, of course, will restrict my brief comments here to the economy, and what the alternatives might entail. But the analysis of the impacts of both programs, if one can talk of programs per se, is very poor, to say the least.

Broadly speaking there has been increasing agreement on a tougher policy with respect to China, what Jake Sullivan referred to as a New Washington Consensus. Many see this as a revival of industrial policy. This is of course suggests some continuity with the Trump policies, even though I would suggest that only with Biden there was a clear plan to re-shore manufacturing jobs, particularly with chips and electric vehicles. Trump basically just hiked tariffs. Both protectionism and the continuity make some liberals (I would say neoliberal progressives, to use Nancy Fraser's term, nervous. For example, Edward Luce's anxiety is that Biden agrees too much with Trump. He says: "both Biden and Trump are vowing to travel in the same direction. But Trump would do so in leaps and bounds."

Note that in all fairness, the US never really stopped doing industrial policy. As noted by Fred Block, even with the problems of the Military-Industrial-Sillicon-Valley Complex, a hidden developmental state. The main new element in the "New" Washington Consensus is really that the US will be less willing to promote economic development by invitation in the case of China. As the IMF policies seem to indicate, for the rest of the world, the old consensus is in place. In that respect, the anxieties of liberals on this are exaggerated.

But that's not all. According to Luce, based on a report* from Moody's, "Trump’s policies would trigger a recession by mid-2025. Unemployment and inflation would jump. The bottom half of US income distribution would suffer the most." He concludes that: "The economic consequences of Trump would be a disaster." This was reinforced letter by 16 Nobel economists warns that: "Many Americans are concerned about inflation, which has come down remarkably fast. There is rightly a worry that Donald Trump will reignite this inflation, with his fiscally irresponsible budgets." This is flatly incorrect. Tax cuts (or their extension) and tariffs wouldn't cause inflation and a recession. Worst case scenario there would be a one time increase in prices, but again the bargaining power of the working class is at low point. So no danger of inflation there. And neither would affect the ability the government to spend. On that Republicans are normally less fiscally conservative when in power than Dems (see old roundtable on that here). And it actually it is a critique that misses the point of why Bidenomics is much better than Trumponomics.

Inflation was not caused by Biden's fiscal packages, as I have insisted several times here (see this paper). And Trump's tax cuts would also not be a problem from that perspective. The point is that Trump would be, in his domestic agenda, more of the trickle down agenda or Republicans going back to Ronald Reagan. Cutting taxes for the wealthy and making it harder for minorities and the poor (often minorities) to access welfare programs. It would be distributively problematic. Inflation is not the risk. The problem with Trump's policies is that they hurt the very working class (many in unions, and certainly white folk) that might vote for him. It would be stupid for unions and other progressives to support Trump.

The good thing about Biden is that he, in part because he had more union connections, and in part because he has moved towards the left (certainly Bernie played a role here), was bold in his fiscal policy, and that might have been instrumental in avoiding a recession (that the Fed was almost engineering). Contrary to Obama, with his mild post-bubble program, and Hillary, Biden has moved to a more traditional Dem (New Deal would be a stretch perhaps) logic of tax and spend.

Eight years ago Hillary had a completely different economic agenda, and that actually explained, to some extent, why Trump ended up winning. I noted that it was likely in this post from before that election, right after a debate, in which I said: "This [election] is going to be way closer than it should be." I also noted that the problem with Hillary was that: "The fact that she has not fully renounced Clintonomics, i.e. financial deregulation, austerity (End of Welfare as we know it) and free trade, is a problem for the progressive base of the party. She walked back some of these, mostly after pressure from the Bernie campaign, but is unclear that these changes would stick."

That these divisions are still relevant within the Democratic Party is clear in the primary in New York that pitied Bowman and Latimer, the former with support from Bernie and the latter from Hillary. Bernie said that "the race 'one of the most important in the modern history of America' and a contest between 'the billionaire class' and ordinary citizens," according to the Financial Times. So if one wants to criticize Trumponomics, the issue is that his agenda is the pro-billionaire one (Wall Street and Silicon Valley agree and have closed the funding gap). Biden is the leftest president since Lyndon Johnson (he is clearly to his right, and LBJ was no commie). He also is not the best possible candidate. He has one unbeatable quality though: he is NOT Trump.

* Mark Zandi is the main author of the report, and he can be seen as another neoliberal progressive, aligned with the pro-business part of the Dems.