My talk last year (2017) at the Critical Economics Summer School of the Unviersidad de Valldolid (in Spanish). It was great to meet and interact with lots of progressive thinkers in Spain.

Tuesday, October 23, 2018

The Global Crisis: Beyond Secular Stagnation

My talk last year (2017) at the Critical Economics Summer School of the Unviersidad de Valldolid (in Spanish). It was great to meet and interact with lots of progressive thinkers in Spain.

Symposium on "Milton Friedman’s Presidential Address at 50"

Here all the links to the papers of the last issue of the Review of Keynesian Economics:

- Thomas Palley and Matías Vernengo: Milton Friedman’s Presidential Address at fifty

- Robert Solow: A theory is a sometime thing

- Robert J. Gordon: Friedman and Phelps on the Phillips curve viewed from a half century’s perspective

- David Laidler: Why the fuss? Friedman (1968) after 50 years

- Roger E. A. Farmer: The role of financial policy

- James Forder: Why is labour market adjustment so slow in Friedman’s presidential address?

- Thomas Palley: Recovering Keynesian Phillips curve theory: hysteresis of ideas and the natural rate of unemployment

- Antonella Stirati and Walter Paternesi Meloni: A short story of the Phillips curve: from Phillips to Friedman… and back?

- Servaas Storm: The wrong track also leads someplace: Milton Friedman’s presidential address at 50

- Louis-Philippe Rochon and Sergio Rossi: The relationship between inflation and unemployment: a critique of Friedman and Phelps

Sunday, October 21, 2018

The budget, the fragile recovery and the next recession

I'm not a forecaster. I do macro, and worked for Wynne Godley at the Levy, but I feel that there are too many dangers in forecasting. Wynne was also, btw, more concerned with what he called medium term scenarios, than pinpointing when a recession would take place. The obvious joke applies here. Economists have predicted 10 of the last 9 recessions. Having said that let me do the exact opposite and throw caution to the wind.

So I'm going out on a limb here. Everybody thinks the recession is around the corner. I'm more skeptical. Let me start by looking at what Martin Wolf has said in his last column, since he seems to be close to what consensus views would argue. He resuscitates old views about confidence cycles. For him: "Bull markets, it is said, climb a wall of worry... so much optimism was already in the prices of financial assets — in the US, above all — that once worry returned they had nowhere to go but down." He suggests that a "jump in risk aversion" might trigger the recession.

Worse, he suggests, following the IMF (that has changed its mind, according to many), that the US government has not helped by embarking on a highly irresponsible, pro-cyclical fiscal expansion on top of what the IMF labels 'already unsustainable debt dynamics'." In other words, expansionary fiscal policy will promote a crash by sapping the confidence of financial markets. Presumably we need sound finance.

The worst risk for him comes from populism, particularly in the US. He notes:

"The biggest shift of all is in the US. Last week, President Donald Trump broke a longstanding taboo by condemning recent tightening by the Federal Reserve. Under him, the US has also embarked on an assault on the World Trade Organization’s dispute settlement system and an open-ended trade war with China."

As I noted in my previous post on this, the biggest risk in my view comes from monetary policy in the context of a relatively fragile and slow recovery, even if it is a very prolonged one. The yield curve (see below; I use the Fed Funds and the 10 year bond rather than the 10-2 spread, since the Fed Funds is more clearly a policy rate, and gives you the result of policy actions) is closing, but if the Fed does not raise the basic rate too fast, there is a chance for the slow expansion to continue.

Note that there are other indicators that suggest that even though the recovery is not great, it may continue for a while. For example, if one looks at Gross Fixed Capital Formation, it is clear that an initial downturn seems to have subsided (like in the mid-1980s), and that the system got a second wind.

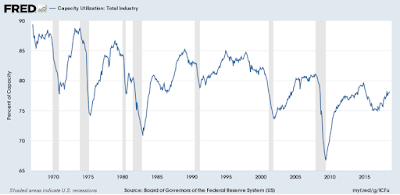

Capacity Utilization in Industry shows a similar picture. Note that this does not mean that the recovery is strong by any means. But last week the news, in spite of the unstable financial markets, were if anything indicating that the economy may continue on this path. I'm referring to fiscal news.

The budget deficit increased. That in and off itself says nothing, since the deficit is endogenous. In part the deficit went up as a result of tax cuts (a lot going to corporations and the wealthy). But also higher spending, quite a bit on defense. So there is a lot to complain about how money is being spent and how taxes are being collected. But that provides a modicum of stimulus. Trump, one should note, actually was more accurate on this than Wolf. He said that there is no fiscal danger, and that the US runs no risk of default (so why would financial markets be concerned with that), since the US can print money. Note that printing money might have consequences, but these are not the ones orthodox economists often suggest (see more here).

Contrary to Wolf I don't think that the trade wars would affect significantly the US economy. It might affect China, and certainly will have effects on the supply chains of US corporations. It might lead to higher prices, but it's implausible that it would bring the economy to a halt. The American economy depends on domestic demand. Nothing much will be affected by the trade war on that front. Also, while I think that student debt (and car loans too) are out of control, and will have implications, it's not clear that these, by themselves would cause a recession, in the way that mortgage loans did last time. They might not affect domestic demand to the same extent, at least not in the short run.

If there is a risk (besides monetary policy) is the persistence of financial speculation and the shadow financial sector, as represented by for example Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs), which have been going to high risk non-financial corporate firms (like Sears). But that does not mean that a recession is around the corner, and this weak recovery can (arguably) prolong itself for a few more quarters. Hey, conceivably it might go on until the 2020 election, giving Trump a serious shot at reelection (and that's not a happy thought).

Thursday, October 18, 2018

US technological hegemony

Where the Digital Things Are

I have suggested for a while here (this entry from May 2011) that deindustrialization in the US has not meant a decline in technological hegemony. Consider big tech digital firms in that respect. From the new Trade and Development Report:

The widening gaps across firms have been particularly marked in the digital world. Of the top 25 big tech firms (in terms of market capitalization) 14 are based in the United States, 3 in the European Union, 3 in China, 4 in other Asian countries and 1 in Africa. The top three big tech firms in the United States have an average market capitalization of more than $400 billion, compared with an average of $200 billion in the top big tech firms in China, $123 billion in Asia, $69 billion in Europe and $66 billion in Africa. What has been significant is the pace at which the benefits of market dominance have accrued in this sector: Amazon’s profits-to-sales ratio increased from 10 per cent in 2005 to 23 per cent in 2015, while that for Alibaba increased from 10 per cent in 2011 to 32 per cent in 2015.For a country in decline, the US corporations are doing surprisingly well. Again, the problem of deindustrialization is one of the consequences for working class people, and inequality. American corporations, capitalism if you prefer, is doing fine. Workers not so much (and hence Trump).

Sunday, October 14, 2018

Brazil is Falling Under an Evil Political Spell

By Thomas Palley (guest blogger)

Brazil is falling under an evil political spell. The leading candidate in the presidential election is Jair Bolsonaro, an extreme right-wing politician. It is as if voters are sleepwalking their way to destruction of Brazilian democracy. Under the spell’s influence, they have become blind to the truth about Brazilian politics and blind to their better nature.

Read rest here.

Saturday, October 13, 2018

Bob Solow on Friedman's Presidential address and the natural rate failure

His full paper was published in the Review of Keynesian Economics. He reminds us that it was a talk to undermine 'eclectic Keynesianism' about which he says:

Milton Friedman's famous presidential address of 1968... aims to undermine the eclectic American Keynesianism of the 1950s and 1960s, the habits of thought to which Joan Robinson attached the (unintentionally) complimentary label of ‘bastard’ Keynesianism. I will only say a little about what that was. In fact, the adjective ‘eclectic’ is meant to remind you that it was not a tight axiomatic doctrine but rather the collection of ideas in terms of which people like James Tobin, Arthur Okun, Paul Samuelson and others (including me) discussed macroeconomic events and policies.More substantively, he argues, correctly my view, that Friedman's misperception model was not accurate, and that the Volcker shock was not caused by any misperception. In fact, Solow suggests that:

So the Fed was in fact able to control (‘peg’) its real policy rate, not for a year or two but for at least six years, certainly long enough for the normal conduct of counter-cyclical monetary policy to be effective.Note that this is the real, not nominal rate. But perhaps Solow's most important conclusion, drawing from the evidence and Blanchard's more recent contributions is that: "findings imply that there is no well-defined natural rate of unemployment, either statistically or conceptually." In that regard, I think that Solow goes further than Blanchard, and I'm glad he does.

Sunday, October 7, 2018

The Brazilian Election or Brazilian Fahrenheit 11/9

#nothim protest in São Paulo

This is, hands down, the most important election in Brazilian recent history. Haven't seen any exit polls, but if the last polls are trustworthy expect a second round between an openly fascistic candidate, Bolsonaro, and the Workers' Party (PT in Portuguese) and Lula's candidate Haddad. Maybe Ciro Gomes has a shot. The US and international media have been part of the problem, in all fairness, for the rise of Neo-Fascism. They suggest that Bolsonaro is not acceptable (like many in Brazil that have protested, pictured above), but they suggest that the Workers' Party is as dangerous and radical, but on the left of the political spectrum. Red scares continue to dominate the media decades after the collapse of Soviet communism. It's a bit tiring.

Note that as I argued in many posts in the past the Brazilian situation is not the result of an economic crisis, fiscal or external. No real economic problem existed. It was, and it still is, a political crisis. Corruption exists, but it is also not the problem. That's what right wingers have used as a political instrument to counter their inability to win elections. The main cause of the political crisis is the result of the moderate improvement in social conditions and inequality during the PT administrations, and the backlash that this has caused in segments of the middle and upper classes.

Interestingly, Dilma Rousseff, the impeached president, is not accused of anything and might have a shot at the Senate seat held by Aécio Neves, her rival in the last election, who is trying desperately to win a seat in Congress to avoid being prosecuted (contrary to Lula, that has been jailed as a result of someone saying he owned an apartment, without a single shred of corroborating evidence; Aécio is recorded asking for a R$2 million bribe, suggesting his cousin would pick it up, since it was a person he could trust and kill if he opened his mouth, and the cousin was later filmed and caught with the money).

It is far from surprising that the Workers' Party is still in the dispute, and might win. Life conditions for the vast majority did improve in their governments (even if there is a lot to criticize in their policies). And they did win the last four elections. They are responsible for a frustrated right wing base that cannot win elections and resents social improvement. But the responsibility for the rise of Neo-Fascism in Brazil should all be placed squarely with the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), the main alternative to PT, that failed to win elections since 1998 (20 years now), and to abide by the democratic rules when loosing.

Besides, the justice system is now seen by many as a corrupted system itself, and the impunity of proven corrupts within PSDB has sapped their support within the middle and upper classes. That empty space has been occupied by Bolsonaro, that claims to be anti-corruption, as Collor did back in the 1990s, and is probably all but. PSDB will probably collapse as the main opposition party after this election. And the middle and upper class are as a result left with a more radical and authoritarian alternative.

In this respect, the Brazilian situation is not very different than the American one discussed by Michael Moore in his last movie Fahrenheit 11/9. Sure there are many reasons for the rise of Trumpism. But the elites in the Democratic Party have an important part in that rise. So-called liberals that did not respect democracy (e.g. the fact that all West Virginia counties went for Bernie, but Hillary got the delegates), or pushed and defended Neoliberal policies (e.g. the shocking role of Obama in the Flint catastrophe) were central to explain what happened (and more important than Russia).

In similar vein, many PSDB intellectuals that had a lot of pride about their fight against the last dictatorship in Brazil, are co-responsible for perhaps helping lead to a new one (since many in the Bolsonaro camp, including him, have suggested they would not accept the results if they loose). Aécio was explicit about not accepting the results of the elections in 2014. And PSDB supported the coup, hoping to be able to win elections as soon as PT was tarnished as corrupt. From jail Lula has defeated them once again. Decent people around the globe now hope he can defeat Fascism too (if he has a chance).

But the blame for this is all in the hands of the supposedly reasonable and well-behaved Brazilian Social Democrats. And the US media, by suggesting that PT is as despicable as the Neo-Fascists is helping them too. If Bolsonaro wins, you know who is to blame.

At any rate if you are interested in digging any deeper go read my previous posts, going all the way back to December of 2015, that chronicle the unfolding of the crisis:

- Goodbye Lula, Hello Failed State

- The Strange Death of Progressive Brazil

- The Mediatic-Parliamentary Coup in Brazil

- Brazilian coup and US misinformation

- Some thoughts on the impeachment and the right wing turn in Brazil

- New York Times on the Brazilian coup... I mean impeachment

- The strange and misunderstood reasons for the Brazilian crisis

Friday, October 5, 2018

Trumponomics and the next recession

Progressives for balanced budgets and free trade

It was the best of times; it was the worst of times. Or that is what you would think if you follow the economics press lately. Sebastian Mallaby has a column on Trumponomics a while ago, suggesting Trumponomics is not working. I wouldn't disagree with the verdict, but the explanation is far from correct, and that is a common feature of discussions of Trumponomics in the media, and frankly by many progressive (not just liberal, in the US sense of the word) economists. On the other hand, you can expect a lot of praise in conservative circles (and bragging from the Trumpsters) about the unemployment level reaching 3.7%, the lowest since the Kennedy/Johnson boom of the 1960s. Many would say we are at full employment, and in a sense they might not be wrong (I think it's debatable; more on that below).

The question is then how things can be both good and bad. First, let me explain the more obvious, the labor market story. The recovery from the 2008 crisis has been long and slow, as it is well-known. And it is unclear what impact Trump's tax cuts will have, but it is highly unlikely that they would lead to any significant acceleration of growth, if past evidence is a good guide. So the current low unemployment level is the result of a process that started with the Obama fiscal package and has proceeded at a slow pace pushed essentially by consumption (after the initial fiscal stimulus). And that's why it has not been a more robust recovery (it remains very slow, even in the two Trump years).

This is reflected in an employment to population ratio that is still below the previous peak, even if now recovering. In other words, the participation rate in the labor market remains relatively low. And, hence, wages have not yet started to pick up significantly, and inflation remains subdued, which casts at least doubts about the meaning of full employment.

This suggests that we would need more fiscal stimulus, and not austerity. That's one concern I have with some critics of Trumponomics. That they presume that fiscal deficits and Trump's tax cuts are both bad. I would suggest that the latter is certainly bad, for distributive reasons. But deficits in the current situation in which the recovery has not raised all boats is far from a problem. I think it was Barbara Bergmann (citing Alvin Hansen) that said that the full employment deficit was the fiscal deficit necessary to bring the economy to full employment. We are probably not there yet. Btw, this is what used to be called functional finance and Trump's critics should learn about it.

Some critics, like Mallaby, are concerned with the trade wars. Here too I'm a bit worried about the positions taken by critics. Progressives have complained about Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) for a long while now. And also criticized the concept of Free Trade (see here for a list of entries in this blog). Mallaby, for example, suggests that the trade war with China, and the new version of NAFTA (USMCA now), which is worse for him than the original (the name for sure, Moreno-Brid suggested at a conference in Mexico this week MEXCUSA, a good pun in Spanish), would reduce productivity and growth.

I still don't have a full picture of the USMCA deal, but it seems that beyond the clauses about North American content and percent being produced with higher wages in the auto industry (both clauses that seem to favor the US and not Mexico), the liberalization of Canadian dairy industry, and tighter restrictions on generic medications (all of which seem to favor US corporations against Canadian citizens), the most important is the one that allows any member country to essentially veto free trade agreements with non-member countries. That is, most likely, a clause for the US to veto FTAs with China.

In that sense, USMCA is just an extension of the trade war with China. I don't want to write much on this, but it seems to me that the US finally decided to revert the opening policy towards China, that harks back to Nixon, and to take the Chinese challenge (and at this point it's just that; I don't see a Sinocentric world any time soon) seriously. In all fairness, it seems to make a lot of sense, from an American security position to make it difficult for Chinese firms to go about the process of catching up, which includes acquiring companies, reverse engineering, violations of copyrights and patents, industrial espionage and more. And yes, there will be disruption of the commodity chains. For example, maybe Apple will move some of its i-Phone production out of China into other developing countries in the region (don't think many manufacturing jobs will return to the US though). But productivity won't suffer much.

If you're concerned with productivity, fiscal policy and its impact on growth should be a greater concern to you. Expansion of demand is what pushes labor productivity (productivity is not the cause of growth, but the result; search the entries on Kaldor-Verdoorn Law in the blog). The slow recovery is the problem.

Finally, I'm still unsure about when the recession will come, but neither the fiscal or trade fronts, which are the ones attacked mostly by Trump's critics seems to be the crucial problem. Monetary policy might be though. If the Fed continues to raise rates, something they suggested they would do, then there is a serious possibility of a crisis ahead. Higher rates would affect the already overextended American consumer, and lead to a recession. Nothing like the last one, I think. And the Fed would be forced to reverse course pretty soon. But the Fed remains independent, also something that old critics of the concept have embraced in the Trump era.

Thursday, October 4, 2018

Kicking away the ladder too: On central banks and development

In case you missed it, and are interested on the topic, the video of my webinar is available here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Surplus approach, Historical Materialism, and precapitalist economies:

New Paper by Sergio Cesaratto on a topic closely related to what he has discussed here before. From the abstract: In the classical economis...

-

There are Gold Bugs and there are Bitcoin Bugs. They all oppose fiat money (hate the Fed and other monetary authorities) and follow some s...

-

By Sergio Cesaratto (Guest Blogger) “The fact that individual countries no longer have their own currencies and central banks will put n...

-

"Where is Everybody?" The blog will continue here for announcements, messages and links to more substantive pieces. But those will...