So if you believe a simplified version of conservative views on the economy, Trumponomics is pretty contradictory (and yes they are contradictory, even if one may doubts about why). Tax cuts should lead to growth, via supply side economics, and the recently proposed tariffs on steel and aluminum do exactly the opposite. Protectionism (not a very good name, I prefer managed trade, as I discussed here before) has made a come back, but while many heterodox economists have suggested that 'free trade' is not always beneficial to all, and those concerned with the fate of manufacturing and the working class in the United States have decried Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) over the years, it seems that the association of these ideas with Trumponomics has made them less keen on the recent tariff proposal.

A typical example is the recent op-ed by Jared Bernstein and Dean Baker in WAPO, and I cite them exactly for my respect for their economic views in general, and their commitment to progressive causes. In their view: "The bigger dangers to our economy are twofold. One, that our trading partners will retaliate by taxing our exports to them, thus hurting a broad swath of our exporting industries, and two, by leading an emboldened, reckless Trump administration to enact more bad trade policy." Essentially, they agree that tariffs would have a negative effect on employment, but perhaps not as big as some Cassandras have suggested, and that this 'bad protectionist' policies would continue. A similar argument can be found in Brad DeLong's op-ed, another progressive economist, in which he argues that the tariff is a tax hike for consumers. Brad, I should note, has recently published a very good book in which he praises the Hamiltonian system, that is, the use of managed trade to promote industrial development (I discussed it here).*

A typical example is the recent op-ed by Jared Bernstein and Dean Baker in WAPO, and I cite them exactly for my respect for their economic views in general, and their commitment to progressive causes. In their view: "The bigger dangers to our economy are twofold. One, that our trading partners will retaliate by taxing our exports to them, thus hurting a broad swath of our exporting industries, and two, by leading an emboldened, reckless Trump administration to enact more bad trade policy." Essentially, they agree that tariffs would have a negative effect on employment, but perhaps not as big as some Cassandras have suggested, and that this 'bad protectionist' policies would continue. A similar argument can be found in Brad DeLong's op-ed, another progressive economist, in which he argues that the tariff is a tax hike for consumers. Brad, I should note, has recently published a very good book in which he praises the Hamiltonian system, that is, the use of managed trade to promote industrial development (I discussed it here).*

It's worth remembering that while on other issues Trumponomics is essentially Reaganomics (low taxes for the wealthy and increased military spending), on trade his views are a break with more recent Republican positions (and hence the push back in his own party against the tariffs) and closer to what many Dems, particularly those connected with trade unions, often defended. He has not signed TPP, has really started renegotiating NAFTA (something Obama promised to do as a candidate, but did not deliver as president) and now has imposed some tariffs (like, btw, Bush, so I'm not suggesting this is unprecedented; just that he has been more consistent on this topic).

Don't get me wrong, I'm not a big fan of Trumponomics, or even in particular of these tariffs. And this will not work probably, but the reasons are not the ones adduced by progressives. Their basic argument is that retaliation by other countries will make them innocuous. In all fairness, the US is already more 'protectionism' (manages trade) than most people understand. The ability to use trade treaties and organizations for defending the country's own advantage is considerably tilted in favor of advanced economies and their corporations that can use loopholes to creatively avoid rules and continue to subsidize their industries (and agricultural sector). The US use of the defense department, again used by Trump, is typical. Poor countries some times lack the basic technical capabilities (lawyers and economists) to face the trade teams of advanced economies. The complexity of the WTO dispute settlement process, the geopolitical role of the US and the importance of US markets for many developing countries render it a very ineffective tool for the interests of less developed economies.

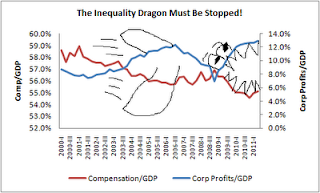

It should not be a surprise that American corporations continue to thrive in international trade (it's the American working class that is in trouble). Manufacturing is doing well, with the support of what Fred Block has termed the hidden developmental state in the US. So the problem is not that tariffs could not work. In all fairness, tariffs together with significant expansion of domestic spending on infrastructure (and more steel demand), with a vigorous defense of trade unions, with higher minimum wages, with policies to improve income distribution, like progressive taxes on the wealthy, to strengthen the domestic market might actually be part of a Hamiltonian strategy of economic growth. Note also that the whole point of imposing tariffs is to depend less on exports and more on domestic markets, so that to some extent retaliation should matter less. A more closed (not closed, but more so, like Keynes suggested in his National Self-Sufficiency piece of 1933) international economic order, to role back of some of the excesses of the neoliberal, pro-corporate globalization process, used to be be, and should be, on the agenda of the left.

The problem, then is less the tariffs per se, and more the fact that the Trumpian agenda is empty, and has nothing for the working class. That was my biggest concern reading the progressive economists complaints about Trump's trade views. Their solutions are to stop protecting patents and professionals, that is more 'free trade,' and a more depreciated currency (I'll leave my skepticism about this one for another post, at any rate I discussed this before). While I'm more sympathetic to the skepticism on property rights, note that China, in part, thrives, exactly because they do explicitly infringe the rules on patents (the first Geely car was a knock off of a Mercedes, and they bought Volvo to have access to foreign technology; there are many examples; it's worth noticing that the US did that in the past too). That would not necessarily be good for American corporations. To weaken doctors, lawyers and other middle (and upper middle) class professionals is certainly not the way out of the hole for the American working class.

It should not be a surprise that American corporations continue to thrive in international trade (it's the American working class that is in trouble). Manufacturing is doing well, with the support of what Fred Block has termed the hidden developmental state in the US. So the problem is not that tariffs could not work. In all fairness, tariffs together with significant expansion of domestic spending on infrastructure (and more steel demand), with a vigorous defense of trade unions, with higher minimum wages, with policies to improve income distribution, like progressive taxes on the wealthy, to strengthen the domestic market might actually be part of a Hamiltonian strategy of economic growth. Note also that the whole point of imposing tariffs is to depend less on exports and more on domestic markets, so that to some extent retaliation should matter less. A more closed (not closed, but more so, like Keynes suggested in his National Self-Sufficiency piece of 1933) international economic order, to role back of some of the excesses of the neoliberal, pro-corporate globalization process, used to be be, and should be, on the agenda of the left.

The problem, then is less the tariffs per se, and more the fact that the Trumpian agenda is empty, and has nothing for the working class. That was my biggest concern reading the progressive economists complaints about Trump's trade views. Their solutions are to stop protecting patents and professionals, that is more 'free trade,' and a more depreciated currency (I'll leave my skepticism about this one for another post, at any rate I discussed this before). While I'm more sympathetic to the skepticism on property rights, note that China, in part, thrives, exactly because they do explicitly infringe the rules on patents (the first Geely car was a knock off of a Mercedes, and they bought Volvo to have access to foreign technology; there are many examples; it's worth noticing that the US did that in the past too). That would not necessarily be good for American corporations. To weaken doctors, lawyers and other middle (and upper middle) class professionals is certainly not the way out of the hole for the American working class.

The political danger of these views, which I think still dominate the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, is considerable. I think, that even if his policies turn out not to be very helpful (for the reasons I outlined, meaning lower wages and protections for workers, lower taxes for the wealthy and corporations and so on) his true dislike of globalization and free trade policies would strengthen his position with working people in the Rust Belt, which were central for his victory (maybe you think it was Russia... oh, well). As I noticed before the election, this would make things so much hard for Dems in elections. I said back in September 2016 that: "Note that this doesn't mean he [Trump] is going to win the election. Demographic changes make it harder for Republicans to win now, since Dems get more of the electoral college to start with. And I hope he doesn't, btw. But there are good reasons to be afraid. This is going to be way closer than it should be." And so it was.

I'm afraid that his trade policies, and the Dems position that effectively are to his right (like Hillary, but not Bernie) would make it more likely (hopefully not enough) for a longer period of Trumponomics than it is acceptable. This suggests that a good chunk of Dems are stuck in the model that Mark Lilla has referred to as identity liberalism (see his book here), and have become vulnerable to right wing populism. It's getting increasingly difficult to have hope in the dark.

PS: For discussions of trade policy see this two previous entries which provide a simple discussion of the Ricardian and neoclassical models of trade and its limitations. I would also recommend the paper by Robert Wade linked here.

* There are many others that have written on this in the last couple of days. Paul Krugman could, arguably enter the list of progressives here, but he has been consistently more of a free trade guy. Krugman complain is more macro than the others. In his view, the Fed would hike rates, since we are close enough to full employment and any additional gains from the tariffs will be eroded, even without retaliation from other countries. In part, that would happen because higher interest rates would lead to inflows and an appreciation of the dollar (see here).

I'm afraid that his trade policies, and the Dems position that effectively are to his right (like Hillary, but not Bernie) would make it more likely (hopefully not enough) for a longer period of Trumponomics than it is acceptable. This suggests that a good chunk of Dems are stuck in the model that Mark Lilla has referred to as identity liberalism (see his book here), and have become vulnerable to right wing populism. It's getting increasingly difficult to have hope in the dark.

PS: For discussions of trade policy see this two previous entries which provide a simple discussion of the Ricardian and neoclassical models of trade and its limitations. I would also recommend the paper by Robert Wade linked here.

* There are many others that have written on this in the last couple of days. Paul Krugman could, arguably enter the list of progressives here, but he has been consistently more of a free trade guy. Krugman complain is more macro than the others. In his view, the Fed would hike rates, since we are close enough to full employment and any additional gains from the tariffs will be eroded, even without retaliation from other countries. In part, that would happen because higher interest rates would lead to inflows and an appreciation of the dollar (see here).

.jpeg)