If everybody was predicting a recession before the employment numbers last Friday,* now it has become an unanimity. The story is of course the uncertainty caused by the tariffs and the collapse of investment (a second story, far behind in popularity, is that profit squeeze, also caused by tariffs to some extent, caused the decline in investment). I should note that most stories in the press are vague about the mechanism for the recession. But when pressed most people fall into the uncertainty story.

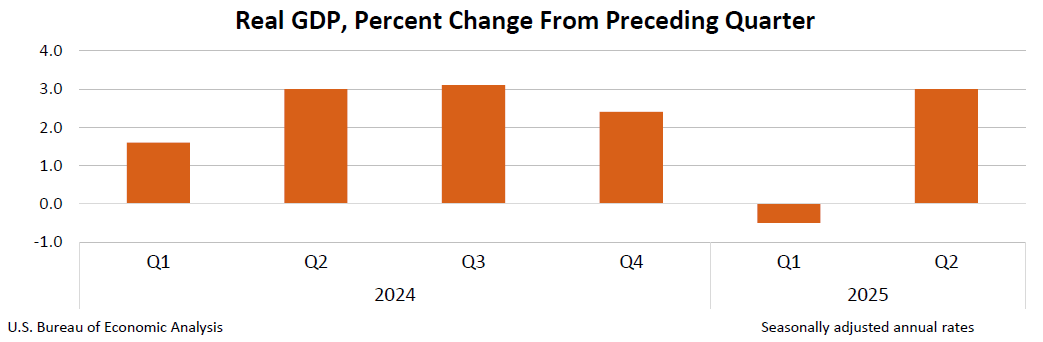

First, let me discuss briefly the numbers. GDP grew significantly in the second quarter, if one looks at the BEA Report, also released last week, at 3% (see figure below). Of course, as noted before, when the numbers of the first quarter come out, the whole story was in the import numbers. Huge increase in the first quarter (imports subtract from GDP, making growth negative), and large decline now, explaining the growth spurt. As noted before, in that same post, GDP is simply slowing down. Ray Fair has suggested that in the last forecast of his model, before the election last year. No surprises there.

A better way of looking this is that growth is slowing down after a spurt that was caused by the rapid -- and I must add, bipartisan -- increase in spending after the pandemic, and the infamous (worst mistake in 40 years, according to Larry Summers) US$ 1.9 trillion fiscal package. The economy is sliding into lower rates of growth, now a little below 2% (see below).

Why was GDP slowing down, and even Fair forecasts suggested that before Trump's election victory, one might ask. The reason is that the fiscal expansion had basically given way to a less expansionist stance, and monetary policy had been tightening over the last two years. In fact, the most troublesome part of the two BEA reports this year is the slowdown in the government spending contributions to economic growth (negative in the first quarter, and only slightly positive in the second; and consistently negative at the federal level), with a large fall on non-defense spending in the second quarter (see this table).Again, whether this would eventually continue is to be seen. It seems that the DOGE/libertarian wing of the GOP has lost internally, but the Big Beautiful Bill was more about cutting taxes (for the wealthy; and spending for the poor) than about expanding spending (even defense spending). This is not exactly Reaganomics (I'm not even talking about the tariffs).

The other thing is the effects of interests rates, which the Fed had also kept in place a couple of weeks ago, prompting lots of insults from Trump, and a renewed defense of the central bank by many progressives (I need to write about the new breed of Free Trade/Central Bank Independence progressives). As I have discussed before, a key variable here is Private Residential Fixed Investment, shown below. As I noted before, only four times this variable became rate of change was negative and a recession did not follow (In the early 50s, because of the Korean War, the late 60s, because of Vietnam, the early 90s, with the dot.com bubble, and in 2023, as a result of Biden's fiscal package, only possible in the post-pandemic context). Now this is again moving dangerously close to the negative space. This is where the big risk of a recession comes from. High interests that affect the ability of households to consume, that is tied to mortgage interest rates (which depend on the Fed policy rates). not surprisingly consumption has also grow sluggishly after an initial decline (even with wages at the bottom still growing more than inflation).

Interestingly enough, on this (and only on this), Trump seems to be right, and Powell wrong, even if you think that Powell is a decent man (I'm not sure anyone would be confused about Epstein... I mean, Trump). Lower interest rates would be important to avoid a recession. So it would be the case with a more robust round of spending on social transfers like we did during the pandemic. But that is certainly not happening. The mood has turned against fiscal policy, even among progressives. Not that there is any risk of a fiscal crisis. On this the MMT crowd is correct.

But as a conclusion: it is NOT the uncertainty of tariffs, or its effect on profits and investment (which is merely reactive to the level of activity). It is macroeconomic policy, or the mismanagement of the macro policy to be more precise, that might cause a recession.

* And yes, before anyone says anything, it was nuts to fire the BLS head. I doubt, however, that he will be able to cook the numbers, and think that even with a crony (I hope not) the BLS is a strong institution that will basically report the numbers, as it has done so far.

.png)