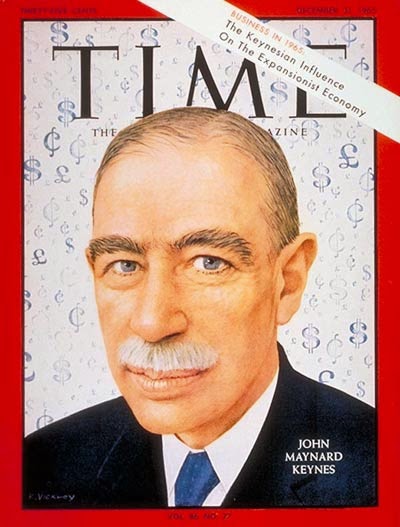

1965: when we were all Keynesians (wink, wink, nudge, nudge, say no more)

Recently the Boston Globe had a

piece on the Leontief Prize shared by Duncan and Lance, but emphasizing to some extent that while the winners are true heterodox economists (for a personal definition of heterodox go

here) and 'real Keynesians' one would think, some well known progressive economists, like Krugman, are not 'real Keynesians.' In many ways, the issue has been discussed

here before (or

here).

Keynesian is one of those labels that is imbued with several meanings, and there are, not surprisingly, many prefixes to denote the particular Keynesian tribe, e.g. neo-Keynesian, post-Keynesian, New Keynesian, Old (Neoclassical Synthesis) Keynesian, sometimes referred in less polite fashion as Bastard Keynesian, classical-Keynesian (Sraffian-Keynesian?), etc. And those are just the ones related to theory, since policies have been referred to as Military Keynesianism or more recently

weaponized Keynesianism, Social Democratic Keynesianism, Pragmatic Keynesianism, and even

Republican Keynesianism. I've been told that Naked Keynesianism is a

thing. Semantic saturation may imply that the very meaning of Keynesian is too vague to have any clear connotation. Plain Keynesianism is an

avis rara.[1]

One way in which Keynesianism is understood is related to its policy implications. The notion that fiscal expansion might be needed to get out of a recession. An idea not discussed in the GT, beyond some vague reference to the socialization of investment. In that sense, there is little doubt that Krugman, and others like him (e.g. Brad DeLong, Simon Wren-Lewis if we stick to those with prominent blogs) are Keynesians. New Keynesians are for fiscal expansion in the particular situation of the zero bound interest rate, in which monetary expansion cannot be pursued. And they have been consistently against austerity policies in the US and in Europe, and political allies of many radical or heterodox Keynesians.

But if policy is the yardstick of Keynesianism, then one must remember that Keynes supposedly argued in the 1944, after a famous Washington meeting with many Keynesian economists in DC, that he was not a Keynesian.[2] Meaning he was not for further stimulus after the war, presumably because unemployment was not going to be a problem. In the same vein, many heterodox Keynesians are often for contractionary policies, including in situations in which the economy is far from full employment. Lance defended in the QA session after the prize that Brazil might need fiscal adjustment since it has an external problem.[3] These would be anti-Keynesian views, if the fiscal expansion policy proposition is the true meaning of Keynesianism.

But obviously the policy perspective, as important as it is, is only a narrow definition of the meaning of Keynesianism. The essential point that Keynes was trying to prove was that, even with price flexibility, the economic system does not have a tendency to the natural rate of unemployment (or the level of full employment, associated with price stability). He was even very clear that the very notion of a natural rate -- Keynes actually referred to the analogous natural rate of interest rather than the unemployment one, which was only discussed by Friedman in the late 1960s -- was a bad idea. By that measure, Keynes himself failed, since the acceptance of the marginalist investment theory, with investment inversely related to the rate of interest, implied that there was a sufficiently low rate of interest that would bring investment to equilibrium with full employment savings. However, once one gets rid of the neoclassical theory of investment, the possibility of persistent unemployment, of unemployment equilibrium (not disequilibrium) is perfectly possible. The system is inefficient and the cause is not an imperfection.[4]

Note that by this definition Keynes himself failed to provide a full explanation of why the system does not tend to full employment, since the notion of a natural rate was still part of his model. In this theoretical sense, Keynesian ideas had to be fully developed later in order to get to the 'real Keynesian' notion of unemployment equilibrium. An many heterodox Keynesians still fail to get that point. Uncertainty, which is often referred as one of the reasons for persistent unemployment,

per se is not a cause for the system not going to full employment. It's just another imperfection. In this case, the group of economists that are 'real Keynesians' is narrow indeed. And it shouldn't be a surprise that many economists that think of themselves as heterodox do like Say's Law, at least in the long run.[5]

I must emphasize that the fact that the number of economists that understand effective demand is very narrow (and even narrower if you add those that get the old classical political economy theory of value and distribution; are we counting 'real Marxists' too?), and that theoretical confusion and error are widespread is not new. The profession was always dominated by a vague and somewhat incoherent defense of the free market forces. Most Ricardian economists were not 'real Ricardians' and to this day readers of Adam Smith miss the point.[6] The combination of factors that allowed for the Keynesian policy consensus between the Depression and the collapse of Bretton Woods were peculiar, and involved not only the fear that capitalism would collapse, but also the existence of an alternative system.

In one sense, I do agree with the message of the Boston Globe piece. The theoretical definition of Keynesianism takes precedence and is more relevant. Without a solid theoretical result, alternative to the mainstream, there is no basis for an alternative policy prescription. Imperfections may allow for Keynesian policies, but they may also suggest that the solution is neoliberal policies of eliminating imperfections (e.g. rigidities in the labor market). 'Real Keynesians' are truly important. On the other hand, it is important to notice that in the age of austerity, the policy dimension of Keynesianism becomes more relevant.

So I'm increasingly favorable to the Keynesians, that might not be 'real' (heterodox), but that promote Keynesian policies. We need more of those around, even if they are not 'real.' Particularly in government positions. For example, the

Keynesian economists in the Kennedy-Johnson administration were certainly not heterodox, and their view of the space for Keynesian policies was built on the notion of rigid wages, and a stable Phillips Curve. All very problematic from a theoretical point of view. But they did the tax cut, the war on poverty and Medicaid/Medicare programs. With enemies like these who needs friends?

[1] Wynne Godley used to say that he was just Keynesian. No prefix.

[2] I'm exaggerating a bit. In the meeting he argued against Abba Lerner's functional finance, even though later he suggested he liked the book in which Lerner's ideas were fully developed. There are many accounts of that meeting, and not all consistent. In one of these, Evsey Domar, who was seating next to Lerner supposedly said to Lerner regarding Keynes non endorsement of expansionary policies that: "he ought to read

The General Theory." The implication is that Keynes was not a Keynesian, at least not under all circumstances.

[3] This view has been defended by many economists that are certainly not neoclassical. Some New Developmental economists suggest that fiscal austerity to control inflation, and depreciation to promote growth are required in the current circumstances in Brazil. A similar view is held by some, arguably heterodox, economists in Argentina and Mexico too. I have discussed extensively

before why I think this is a misguided policy (e.g.

here or

here).

[4] Hence the relevance of the

capital debates. Keynes suggestion that the system did not have a tendency to full employment in chapter 19 of the GT, and his arguments there are based on the effects of lower wages and prices on income distribution and on debt. These arguments suggest that the natural (full employment) rate might be a weak attractor of the system. The capital debates eliminate the existence of the full employment rate as an attractor.

[5] And it's not just the heterodox that are often confused, and provide only partial and incomplete critiques of the mainstream. That's even more common among the mainstream. It's particularly true of the younger generation of mainstream economists. Most neoclassical economists do not understand neoclassical economics. I would suggest that reading Piketty gives you a sense of how little neoclassical economists understand neoclassical theory. The same would happen, for example, if one reads Noah Smith's blog. On this go

here.

[6] Brad DeLong dismisses Marx because he embraced the labor theory of value (LTV), but sings the praises of Adam Smith, as if he didn't also use the LTV. See

here.