So we're having a discussion about the new Management College at Bucknell. Traditionally resources are the main problem in the relation between business schools and economics departments. Often, as in the University of Utah, were I was before, there are issues related to the curriculum, in particular if the economics department is heterodox. In a liberal arts environment, the issues are not only associated to resources, but also to the teaching of what is assumed to be more practical knowledge or marketable skills in a

milieu in which the main goal of education is to develop the essentials for civic life, where critical thinking and the ability of learning how to learn are at the center of the curriculum.

Is it possible? Or would the management goals undermine the liberal arts experience. Note that many think that liberal arts education is doomed anyway (an

old topic by the way). The fear is that students cannot (given tuition costs) afford the luxury of an education for education's sake, but need 'practical knowledge,' that would be useful in the market (the market analogy was used freely in the faculty meeting). I have my doubts about how useful 'practical knowledge' is compared to a broad education that prepares citizens to think independently and critically about the world, but that's difficult to evaluate, I guess.

The experience of Cambridge and Oxford I think is relevant for the US liberal arts institutions, in particular the former which was central for heterodox economics until the 1970s or so. They did not have business schools until recently. In Cambridge the management program was in the engineering school and only in the 1990s it became independent as an institute, eventually becoming a school in this century (in Bucknell the major, became a school and now will turn into a college, but the idea is the same, it will get more independence to raise funds, hire faculty and establish its own curriculum).

The decline of heterodox economics at Cambridge, and its transformation into a second rate neoclassical department, which deserves thorough analysis (something I'm certainly not capable or planning to do), took place more or less at the same time that business became more relevant. The old Cambridge Keynesians retired (and passed away) in the 1970s and 1980s. Richard Kahn, Austin and Joan Robinson, Piero Sraffa, Nicholas Kaldor, and the neoclassical, but still Keynesian James Meade (by the way, the only one to get the Sveriges Riksbank prize in memory of Alfred Nobel) were the key figures. Harrod was at Oxford, but in a sense is a member of the same group, and perhaps the same applies to Hicks (the other neoclassical Keynesian winner of the Sveriges Riksbank prize), also from Oxford. Wynne Godley was the head of the Department of Applied Economics, brought from the Treasury by Kaldor, but even before he left in the 1990s, his team was defunded after Thatcher's conservative victory. A few token heterodox economists were left in the department, and a few still resist, but it is not a place were heterodox, critical thinking is taken seriously.

Note that I'm not suggesting that the rise of management and business are the cause of the demise of Cambridge Keynesianism. Both changes are very likely simply, and only in part, explained by the same general move, in British society and around the world, to embrace a market friendly ideology. While I'm, as I noted, skeptical about the value of 'practical' education, and cannot say for sure whether the liberal arts alternative is better, I've a fairly good idea about the value of heterodox economics.

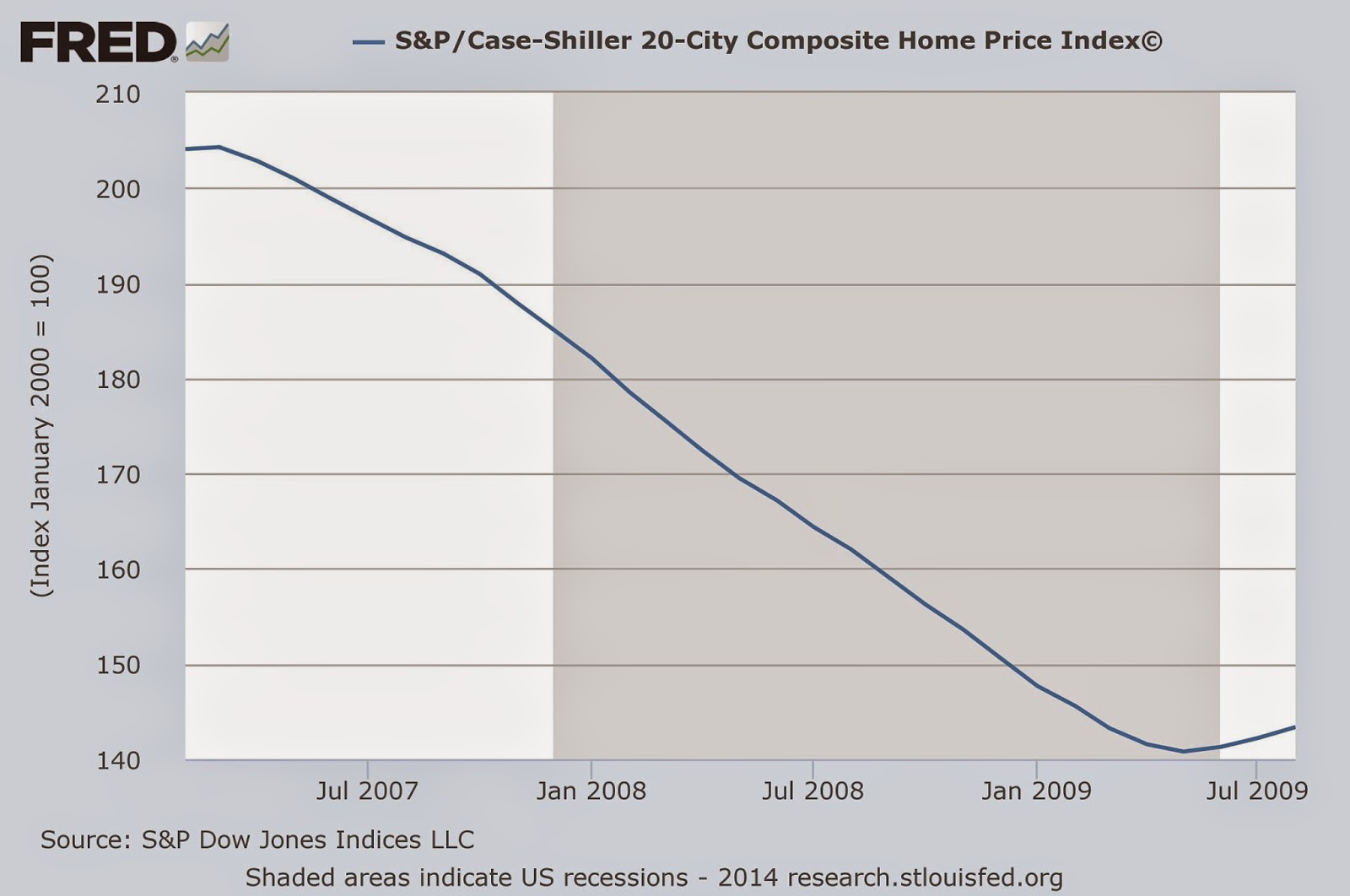

The kind of economics that the old radical Keynesians taught at Cambridge is a better tool to understand the world than the neoclassical alternative that the department there embraced. Note that Godley was one of the few that actually forecasted the Thatcher recession (and probably got punished for that), as well as noting the limits of the dot.com boom and the housing bubble that led to the 2008 crisis (see

here or

here for his prescient views on the euro). Most of my heterodox teachers that were directly or indirectly influenced by the Cambridge Keynesians were not surprised by the crisis that left the mainstream of the profession puzzled. I would say that heterodox economics has practical value indeed. My feeling is that a liberal arts education is often more practical than practical knowledge.