Just a brief note on the whole firing of Comey scandal that is still unfolding, and the incredible degree of anxiety on the left, which somehow thinks this means that there is a 'pee' tape and that Trump will be eventually impeached (here, for example; too many of these). This is at least the second event compared to Nixon's firing of the Attorney General, the infamous Saturday night massacre. The other being the firing the Acting Attorney General Sally Yates.Original post here, from 2 years ago.

All of these is very unproductive and dangerous for progressives in my view. It emphasizes an interpretation of the election that is deeply flawed. That Hilary was a strong candidate, that she was progressive, that she would have won (yeah, I know she did win the popular vote; but that's not the way it works) if Comey didn't discuss the emails days before the election, or the Russians didn't hack her campaign, or if Wikileaks didn't expose them.

It exempts the Dems from being just the other pro-business, slightly less crazy, but pro-business nonetheless, pro-free-trade, pro-Wall-Street party. It reinforces the already strong Neoliberal wing of the Party, that with the help of Obama and the Clintons (all making huge amounts of money in the speaking circuit) elected Perez for the DNC, and might end up with another candidate that will loose the election in the Rust Belt (here and here for my views on the election).

The real danger is eight years of this madness (and my guess, that's much more probable than an impeachment right now), unless progressives within the Democratic Party take over. So sure, investigate, resist, but please, pretty please, let's stop with this notion that all was the result of Russia, and that the Neoliberal wing of the Democratic Party is blameless.

Wednesday, March 27, 2019

The Mueller Report

Perhaps worth reposting what I said about Russiagate, now that the Mueller Report led to no additional indictments and validated the No Collusion slogan we're going to hear for the next year and a half.

Friday, March 22, 2019

Bretton Woods and corporate defaults

In the Eatwell and Taylor book, Global Finance at Risk, they had, I think, a graph with the percentage of corporate bonds in default in the US (I don't have the book here, it's my office). I think this is a close one, with data that is more recent (from this Moody's report).

The graph shows corporate bond default rates (and also the speculative-grade bond defaults). Note that defaults fall significantly during the Bretton Woods era of capital controls and low interest rates.

The graph shows corporate bond default rates (and also the speculative-grade bond defaults). Note that defaults fall significantly during the Bretton Woods era of capital controls and low interest rates.

Sunday, March 17, 2019

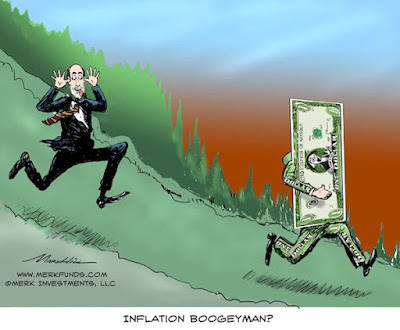

Galbraith on MMT and the Hyperinflation Boogeyman

From his recent piece: "Does this mean that 'deficits don’t matter'? I know of no MMT adherent who has made such a claim. MMT acknowledges that policy can be too expansionary and push past resource constraints, causing inflation and exchange-rate depreciation – which may or may not be desirable. (Hyperinflation, on the other hand, is a bogeyman, which some MMT critics deploy as a scare tactic.)"

Also, this: "And MMT is not about Congress ordering the Fed to use its “balance sheet as a cash cow.” Rather, it is about understanding how monetary operations actually work, how interest rates are set, and what economic powers the US government has. This, in turn, requires recognizing that the dual mandate is not a collection of empty words, but something that can – and should – be pursued on a regular and sustained basis.

There are practical, straightforward, and realistic ways for policymakers to meet this mandate. Implementing them would strengthen the country, not bankrupt it. And, contrary to opponents’ fears, global investors would not flee in terror from US government bonds and the US dollar."

Tuesday, March 12, 2019

Lara-Resende and MMT in the Tropics

So André Lara-Resende, who I discussed here before, is again writing on the crisis of macroeconomics (in Portuguese and you might need to have a subscription), and now instead of embracing the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level (FTPL), has supposedly embraced Modern Money Theory (MMT). Many US MMTers cheered this as a demonstration of the reach of MMT in other countries. I would be less cheerful.

Lara-Resende, let me explain to non-Brazilian readers, was a student of Lance Taylor at MIT, and then a professor at the Catholic University in Rio, being a key author of inertial inflation, an heterodox view of inflation, that was central for the failed Cruzado Stabilization Plan back in 1986. He then participated in the successful stabilization of the economy with the Real Plan, when Fernando Henrique Cardoso was the finance minister in 1994, and during the latter's presidency a short lived president of the development bank (BNDES, in the Portuguese acronym) -- and not the central bank as many in the US have suggested (that was Persio Arida, his frequent co-author on inflationary inertia). Btw, he fell as the head of the bank because he was recorded in conversations with the president (Cardoso) on issues related to the privatization process of the telecommunications sector, in which they seemed to favor a particular group. The development bank during this period was essentially used to promote privatization as a part of the so-called Washington Consensus policies. Also, by the 1990s all the economists from the Catholic University had adhered to the Washington Consensus, and moved away from heterodoxy in the same way Cardoso distanced himself from Dependency theory, and still remain essentially aligned with neoliberal policies to these days. Lara-Resende included, as we will see.

Note that he does say that the four pillars of the new macro are that money and taxes are connected, that the government has no financial constraint, but only a real (capacity) constraint, that money is endogenous (the central bank sets the interest rate), and that the Domar rule holds and stability of debt-to-GDP ratios require the interest rate to be lower than the rate of growth. He also says inflation is all about expectations, and the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) does not hold, something he had already said in his previous op-ed. Many (too many) interpreted this as being Chartalist Money, Functional Finance and Endogenous Money and as such as a version of MMT. Including some analysts in Brazil, with whom I fully agree on their critiques of Lara-Resende's policy conclusions, like the sharp critique by Guilherme Haluska here (also in Portuguese). Note, however, in my previous post on him, that he thought that the FTPL was an heterodox view of the macroeconomy, and he is explicit in his new op-ed that his ideas follow from his last book, in which he defends the FTPL.

In his book what he refers to "heterodox" is the experience with alternative monetary policies after the 2008 crisis, meaning Quantitative Easing, simply because it does not follow the QTM. In his words, from the 2017 book: “The result of the heterodox policies of the central banks in advanced economies, after the financial crisis of 2008, raised serious doubts about some fundamental points of the foundations of macroeconomic theory" or in the original if you don't trust me as a translator (I don't): "O resultado da experiência heterodoxa dos Bancos Centrais dos países avançados, depois da crise financeira de 2008, levantou sérias dúvidas sobre alguns pontos fundamentais da teoria macroeconômica." He does say that one of the pillars of the new macro paradigm is in his 2017 book, but my guess is the ideas are essentially the same. He used the language of MMT, and cited Knapp and Lerner to promote the same neoliberal policies of the 1990s, and the same ideas he defended a couple of years ago using FTPL.

So it is clear that the pillars are essentially of some weird New Classical story of the FTPL, in which fiscal dominance is central to the argument, and there is endogenous money, because of the neo-Wicksellian twist in modern macro. Yes, the QTM does not hold, but it is the expectations about future inflation that matter, and those are tied, in Lara-Resende's views, to fiscal policy (or at least were two years ago). The argument is the fiscal dominance one, that monetary policy has to deal with the unsustainable debt, so inflation is a fiscal phenomenon, and fiscal adjustment is needed. He was and is for austerity! He does use an MMT rhetoric and cites Abba Lerner for sure (more on that below), and that's a testament of the current relevance of MMT and its role in shaping the Bernie and Ocasio-Cortez's progressive views (something positive as I noted in my last post).

His argument is that Brazil is on the wrong side of the Domar stability condition, and, hence, the debt-to-GDP ratio is increasing (in domestic currency), and that something has to be done about it. Not sure why. Note that I always say that in domestic currency there is no default, and one of my complaints about MMT is that they do not pay attention to debt in foreign currency (at some point Warren Mosler was against capital controls and for flexible exchange rates, since the former were not necessary and the latter would solve external problems). But Brazil is not borrowing in foreign currency, and is sitting on top of a mountain of foreign reserves (something like US$ 380 billion, last time I checked, someone correct me if I'm wrong). Then he argues that inflation is all caused by excess demand in the developmentalist period, the period from the 50s to the 80s. However it is unclear why that is still a problem, or why there was excess demand, if it wasn't as a result of fiscal policy.

Fiscal reform, and, in particular, the pension reform are needed not to raise revenue (here is an MMT theme), in his view. He suggests that the reasons are that the pension system is unfair, and that in Lerner's fashion [sic] tax cuts are needed to promote the reduction of bureaucracy and allow for the expansion of more effective private investment.* These should be complemented with trade liberalization, a lower interest rate with a digital currency (bitcoin?) and fiscal adjustment, because the State is "bloated, inefficient and patrimonialist" (in the original: "Estado inchado, ineficiente e patrimonialista").

Lara-Resende, let me explain to non-Brazilian readers, was a student of Lance Taylor at MIT, and then a professor at the Catholic University in Rio, being a key author of inertial inflation, an heterodox view of inflation, that was central for the failed Cruzado Stabilization Plan back in 1986. He then participated in the successful stabilization of the economy with the Real Plan, when Fernando Henrique Cardoso was the finance minister in 1994, and during the latter's presidency a short lived president of the development bank (BNDES, in the Portuguese acronym) -- and not the central bank as many in the US have suggested (that was Persio Arida, his frequent co-author on inflationary inertia). Btw, he fell as the head of the bank because he was recorded in conversations with the president (Cardoso) on issues related to the privatization process of the telecommunications sector, in which they seemed to favor a particular group. The development bank during this period was essentially used to promote privatization as a part of the so-called Washington Consensus policies. Also, by the 1990s all the economists from the Catholic University had adhered to the Washington Consensus, and moved away from heterodoxy in the same way Cardoso distanced himself from Dependency theory, and still remain essentially aligned with neoliberal policies to these days. Lara-Resende included, as we will see.

Note that he does say that the four pillars of the new macro are that money and taxes are connected, that the government has no financial constraint, but only a real (capacity) constraint, that money is endogenous (the central bank sets the interest rate), and that the Domar rule holds and stability of debt-to-GDP ratios require the interest rate to be lower than the rate of growth. He also says inflation is all about expectations, and the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) does not hold, something he had already said in his previous op-ed. Many (too many) interpreted this as being Chartalist Money, Functional Finance and Endogenous Money and as such as a version of MMT. Including some analysts in Brazil, with whom I fully agree on their critiques of Lara-Resende's policy conclusions, like the sharp critique by Guilherme Haluska here (also in Portuguese). Note, however, in my previous post on him, that he thought that the FTPL was an heterodox view of the macroeconomy, and he is explicit in his new op-ed that his ideas follow from his last book, in which he defends the FTPL.

In his book what he refers to "heterodox" is the experience with alternative monetary policies after the 2008 crisis, meaning Quantitative Easing, simply because it does not follow the QTM. In his words, from the 2017 book: “The result of the heterodox policies of the central banks in advanced economies, after the financial crisis of 2008, raised serious doubts about some fundamental points of the foundations of macroeconomic theory" or in the original if you don't trust me as a translator (I don't): "O resultado da experiência heterodoxa dos Bancos Centrais dos países avançados, depois da crise financeira de 2008, levantou sérias dúvidas sobre alguns pontos fundamentais da teoria macroeconômica." He does say that one of the pillars of the new macro paradigm is in his 2017 book, but my guess is the ideas are essentially the same. He used the language of MMT, and cited Knapp and Lerner to promote the same neoliberal policies of the 1990s, and the same ideas he defended a couple of years ago using FTPL.

So it is clear that the pillars are essentially of some weird New Classical story of the FTPL, in which fiscal dominance is central to the argument, and there is endogenous money, because of the neo-Wicksellian twist in modern macro. Yes, the QTM does not hold, but it is the expectations about future inflation that matter, and those are tied, in Lara-Resende's views, to fiscal policy (or at least were two years ago). The argument is the fiscal dominance one, that monetary policy has to deal with the unsustainable debt, so inflation is a fiscal phenomenon, and fiscal adjustment is needed. He was and is for austerity! He does use an MMT rhetoric and cites Abba Lerner for sure (more on that below), and that's a testament of the current relevance of MMT and its role in shaping the Bernie and Ocasio-Cortez's progressive views (something positive as I noted in my last post).

His argument is that Brazil is on the wrong side of the Domar stability condition, and, hence, the debt-to-GDP ratio is increasing (in domestic currency), and that something has to be done about it. Not sure why. Note that I always say that in domestic currency there is no default, and one of my complaints about MMT is that they do not pay attention to debt in foreign currency (at some point Warren Mosler was against capital controls and for flexible exchange rates, since the former were not necessary and the latter would solve external problems). But Brazil is not borrowing in foreign currency, and is sitting on top of a mountain of foreign reserves (something like US$ 380 billion, last time I checked, someone correct me if I'm wrong). Then he argues that inflation is all caused by excess demand in the developmentalist period, the period from the 50s to the 80s. However it is unclear why that is still a problem, or why there was excess demand, if it wasn't as a result of fiscal policy.

Fiscal reform, and, in particular, the pension reform are needed not to raise revenue (here is an MMT theme), in his view. He suggests that the reasons are that the pension system is unfair, and that in Lerner's fashion [sic] tax cuts are needed to promote the reduction of bureaucracy and allow for the expansion of more effective private investment.* These should be complemented with trade liberalization, a lower interest rate with a digital currency (bitcoin?) and fiscal adjustment, because the State is "bloated, inefficient and patrimonialist" (in the original: "Estado inchado, ineficiente e patrimonialista").

With friends like these, who needs enemies?

* It's true that Brazil has relatively high levels of taxes, in comparison to developing countries, but the problem is not that they are high, per se, but instead that they are regressive.

* It's true that Brazil has relatively high levels of taxes, in comparison to developing countries, but the problem is not that they are high, per se, but instead that they are regressive.

Saturday, March 9, 2019

MMT and its Discontents: Again (Wonkish and Longish)

I have discussed Modern Monetary Theory in this blog for years (going back to April 2011, when I first found use of the term, to the most recent earlier this year after Olivier Blanchard American Economic Association presidential address last January), and have known the main MMTers going back to at least the mid-1990s, when I was at the New School and working as research assistant to Wynne Godley at the Levy Institute. I guess, I can be seen, to use the term employed by Doug Henwood in his recent Jacobin piece, as a fellow traveller (like Jamie Galbraith), even though I've been critical of some aspects, in particular when applied to developing countries (more on both Henwood and MMT issues in developing countries below).

There are many critiques, which deal with both theoretical issues, mostly concerned with the Functional Finance aspects of MMT, and with the policy and political effects of MMT advising to the left of center Democratic presidential candidates. Note that I will not try to define MMT precisely, since it is a hybrid of economic theories and policy proposals. I would assume that at core it is composed by the ideas of Chartalist and Endogenous Monetary views, Functional Finance, and an Employer of Last Resort (ELR) program as suggested by Greg Hannsgen in his recent presentation at the Eastern Economic Association (EEA), in sessions we co-organized (with the presence of Randy Wray presenting Stephanie Kelton's slides and Josh Mason; Stephanie was with Bernie at the rally in Brooklyn).

My comments will be, for the most part, directed at issues that fall within the Functional Finance part of MMT, and mostly about developed economies like the US (although, I'll have something to say about developing countries like Argentina or Brazil). I might add that Randy suggested that Functional Finance was a late addition to MMT, since this ideas were not known by MMTers in the mid-1990s or so. I think that the original source for the Functional Finance story was Ed Nell, who organized a conference at the New School back in 1997, I think, with Bob Eisner, and many other Old Keynesians. I had read Abba Lerner and Evsey Domar foundational papers in Ed's classes, and I think his influence on MMTers in this area is reasonable to assume.

Let me start with Paul Krugman's critiques of MMT, which have been clear and perhaps the most widely read (but there are many, including critiques by Tom Palley and Sergio Cesaratto here in the blog). So Krugman, in one of his most recent posts, starts by showing that there are many levels of the fiscal deficits that are compatible with full employment (not sure who thinks that this is wrong; I would add the same is true about the rate of interest, and that there is no natural or neutral rate of interest, a point that Keynes made back in the 1930s, and that is coherent with the capital debates, and, hopefully, it will be clear why this is relevant below). Then he argues more problematically, in my view, that crowding out is a serious concern, in his words: "The question then becomes one of tradeoffs: would the things the government could buy with a higher deficit be worth the lost private investment due to a higher interest rate?" But he knows well that the crowding out effect is empirically (if not theoretically) irrelevant, since investment is not particularly responsive to interest rates (he knows it's all about the accelerator); then he moves to the issue of the natural rate itself.

He seems to think two things (he can certainly correct me if I'm wrong). One, that MMT requires that you use monetary policy in order to achieve full employment. Two, that if you are in a situation of like the zero-lower bound, then the central bank cannot bring you back to full employment. That is, her assume that, using his own graph, the economy would be in position A.

Note that by his own argument you can go back to a point like B, with full employment by pursuing expansionary fiscal policy (be that an ELR or something else like traditional fiscal policy to expand infrastructure spending, for example; on this I should say that Randy suggested that he thinks traditional fiscal policy might be inflationary, and that's something perhaps would be compatible with Krugman; he noted how Minsky suggested that an ELR can be used as a buffer to control inflation). That is the IS would move up.

So it's unclear what the fuss is all about. If it is because the Fed could, in the MMT story (not sure Functional Finance authors would say that), print money to finance the deficits and bring the economy back to full employment, then the concern might be that it would be inflationary, in a Monetarist sense that printing money might be the cause of inflation. But that does not seem to be his preoccupation (I dealt with the issue of monetization of debt back in May 2011 in a reply to Krugman, who was back then, not surprisingly, criticizing MMT). His concern seems to be that the rate of interest would not go up. But of course, there could be a flat interest rate close to zero, a horizontal monetary policy (MP) line, and the expansion of the IS could be achieved bringing the economy to full employment (right below the C and B points with a zero interest rate).

But that doesn't seem to be the issue either. My guess is that he thinks that the problems is more like the one below, from an older post by him, in which the natural rate of interest is negative (my discussion of that here), and the Fed cannot lead the economy to full employment.

So his point is that the Fed cannot make it because it cannot bring the economy to the natural rate of interest, the one that is compatible with full employment and stable prices. He then goes on to criticize Stephanie on her critique of the natural rate, and tells us that: "So what purpose does claiming that the natural rate is a meaningless concept serve? It looks to me like sophistry – word games intended to confuse what should be a simple issue."

I'm not sure what Stephanie said about the natural rate, but I think it is well-established that the natural rate concept is problematic (note that on this some MMTers have said things I would disagree; e.g. Forstater and Mosler suggest here that the natural rate of interest is zero; my discussion of that here). So I think the position that Krugman attributes to her is correct. Paul Samuelson would agree, as he did when he admitted that the capital debates had shown that neoclassical parables cannot hold (on the capital debates read this old post). So let me explain it briefly. There is no sophistry, just pure logic.

The capital debates show that with factor price reversals, when one good can be said to be capital-intensive at one level of the wage-profit ratio, and labor intensive at another level of the same ratio, there is no monotonic inverse relation between investment and the rate of interest. The investment schedule could look like the one below (my graph), with portions that have a negative slope and some in reverse, and if savings (determined by the level of income as in Keynes' principle of effective demand, rather than a Ramsey inter-temporal model) is given as in the graph below, then there might be no natural rate of interest. Keynes was explicit about that in the General Theory. That means that the monetary authority can set the rate of interest, what Keynes referred to as the normal rate, that was conventional, and that fiscal policy can be used to bring the economy to full employment. Btw, I think that overall Krugman and Kelton agree on that. Krugman says he's defending the theory, not the policy proposals, since he thinks they agree on that.

The point is NOT that the state can do whatever it wants, even though it has a lot of space, but that at the end of the day monetary policy is central for the ability to pursue fiscal policy, and the monetary authority can keep (unless it's forced by law not to do it; and that would bring up the discussion about the rise of the neoliberal idea of independent central banks) interest rates low enough to allow for fiscal expansion without debt growing at a very fast pace. Think of Marriner Eccles during the New Deal (chairman of the Fed at that time; search the blog for more on that). This is the argument that Josh Mason did, in a different way in our session with Randy at the Easterns. Note, also, that even though politically it was acceptable for the Fed to keep interest rates low, at 2.5 percent during the Depression and World War II, by the 1950s political pressures by financial markets and rentiers forced the Fed-Treasury Accord, and things changed (even though rates remained relatively low).

I'll comment briefly on two additional critiques of MMT, the one by Larry Summers, the ex-Treasury Secretary and advisor to the Clintons and Obama, and the one by Doug Henwood, an influential Marxist (see my discussion of his comments, and others, on Marx for the New York Times here), and writer of a very good book on Wall Street. I am sorry to say that both have too many arguments of authority and ad hominem attacks on some MMT authors, which I'm not interested in discussing. But there are a few substantive issues. One is the danger of inflation (that I'm glad Krugman seemed less keen on) and the others are on MMT and developing countries, and the political relevance and practicality of MMT proposals (here most critics have in mind the Bernie/Ocasio agenda of Medicare for all, cheap or free college tuition in public institutions, a jobs guarantee, and a Green New Deal).

I'll start with Henwood. His major issue is inflation, I would say. He says: "That brings us to the next problem: inflation. When the printing presses run freely, it’s not only reactionaries who think that runs the risk of spiraling prices. As I was researching this piece, many people to whom I described MMT, from Democrats to Marxists, brought it up as a worry. MMTers are coy about the topic — they never say how much is too much, and they profess great confidence in their ability to control it." Let me start by saying that inflation has not been a problem in 40 years, while wage stagnation is a central one. But if one is concerned about it, at least one should get the correct analytical tools to discuss it.

He tells us that: "The standard view of the Weimer inflation is that the German economy, severely damaged by World War I and forced to make huge reparations payments to the victors, wasn’t up to the task — it just didn’t have the productive capacity, and its citizens were both unwilling and unable to pay the necessary taxes. So instead the government just printed money and spent it, not only to pay its own bills, but to support bank lending to the private sector." First, that's NOT the standard view of the hyperinflation in Germany. You can read here the standard story, and I cite even a conservative historian like Niall Ferguson admitting that the monetarist story embraced by Henwood is NOT the dominant view among historians. The notion that the economy was at full capacity (didn't have productive capacity) and that printing money caused inflation is what Cagan thought about it. A more refined and somewhat structural story is the dominant view actually. In my view, it is clear that debt in foreign currency (not domestic), and, hence, the external problems of the current account, that forced depreciation, together with wage resistance are at the core of the hyper., German and many others.

In addition, it's worth emphasizing that the US is not Weimar Germany, in the sense that even with much larger fiscal deficits, debt would still be in domestic currency, and no significant pressure for depreciation would arise. The role of the dollar as reserve currency is not really under significant jeopardy. Certainly, there might be questions of inflation if we reach full employment, and that's a different issue (I'll come back to the topic below when I discuss Summers and the political feasibility of MMT sponsored plans). But the kind of alarmism of even suggesting that the US would be on the verge of hyperinflation is not serious. I won't comment on other primary mistakes like the notion that the rise of Nazism is associated to the hyper, when it is clearly connected to the Depression and deflation a decade later.

Henwood is on firmer ground, actually, when he discusses the external limits. Yes, indeed, for most developing countries like Argentina or Brazil, the ability to pursue expansionary fiscal policy is severely limited by the balance of payments constraint. Considerably before full employment, the patterns of consumption and investment may require too many imports, particularly of intermediary and capital goods, and even with capital controls, interest rates might be hiked to avoid capital flight and depreciation. Depreciation does solve the external problem, often by throwing the economy in a recession, and not because it stimulates exports. There is extensive discussion of that in the blog about it. Sometimes MMTers sounded like New Developmentalists in Latin American suggesting that depreciation would solve the external constraint and that capital controls were not even necessary. I don't think Randy believes that (or Stephanie), but it was certainly something that Warren Mosler believed in the past (whether he changed his mind I can't tell). But again the debate seems to be about the feasibility of MMT in the US (that's why I didn't emphasize in my comments on the roundtable the differences of debt in domestic and foreign currency, something I always do, as noted by Josh).

So that leads me to the last critique, the one by Larry Summers in his recent piece in WAPO. Summers says that: "Modern monetary theory... is the supply-side economics of our time" and that "these new ideas [about the importance of fiscal deficits] are being oversimplified and exaggerated by fringe economists who hold them out as offering the proverbial free lunch: the ability of the government to spend more without imposing any burden on anyone." He also says in Monetarist fashion that printing money would lead to hyperinflation. In his words: "As the experience of any number of emerging markets demonstrates, past a certain point, this approach leads to hyperinflation. Indeed, in emerging markets that have practiced modern monetary theory, situations could arise where people could buy two drinks at bars at once to avoid the hourly price increases. As with any tax, there is a limit to the amount of revenue that can be raised via such an inflation tax. If this limit is exceeded, hyperinflation will result." Again, emerging markets, like Germany, borrowed in foreign currency, that they cannot print. It was often the depreciation of the currency, the increase in the prices of imported goods, and the wage resistance of workers that led to hypers, and the central bank printed money afterwards, with money being endogenous. A foreign debt or external problem, not a fiscal one.

But there might be a danger of inflation (not hyper) if Bernie wins the election and manages to pass Medicare for all, free college, a Job Guarantee and actually spend some money on infrastructure, and to do something about global warming, without significant reshuffling of spending. Here is where I think the question of the supposed naïveté of MMTers comes to play, with Henwood suggesting that they shirk the question of fiscal choices, and with Summers saying they resemble voodoo economics, the supply-side of the left (mind you supply-siders are many things, but certainly not naïve). I think, first of all, that the dangers of inflation are exaggerated, for several reasons. First, the labor market is not as tight as normally suggested. The number of people discouraged and out of the labor force is relatively large. Second, there are positive effects of growth on productivity (the Kaldor-Verdoorn effect, search on the blog too), so the supply constraint is not fixed, rigid at one given level (people said the natural rate of unemployment was 5 percent or higher just a few years back; again check past blog posts). Third, the bargaining power of unions, and workers in general, is not particularly strong, and it would take sometime to pick up.

More importantly, there is no chance that a Bernie presidency (and that's in and of itself a big if) would have both houses and could implement even a little bit of the program presented. Mind you if it happened we would probably get to full employment in a couple of years, and get increases in wages, and perhaps some inflation. But some inflation might be good, in particular if it allows for higher real wages, something sorely needed. How much inflation? Difficult to say, but the structure of the Fed is not going to vanish, and higher rates would be used to discipline the labor class, with the support of many neoliberal Dems. The limit will come probably before full employment and the capacity limit of the economy is reached (yes inflation happens before the capacity limit, because it's often cost push, and the sort of demand pull stuff Summers and Henwood are afraid about is not that common). In other words, the limits to fiscal expansion would be political, not economic, and there is no reason for the left to be up in arms against an imaginary enemy. Hyperinflation is like the the windmills for the Quijote. The giants to attack are actually the ones pointed out in the progressive agenda, like lack of spending on health, education and the environment, and MMTers have been instrumental in getting these ideas in the political discourse, and moving the Dems to the left.

But taxes matter too. Here is where the MMTers refusal to acknowledge that taxes on the wealthy are necessary is a political mistake (not all I've been told, but some for sure, as I've heard that criticism). Note that from the logical point of view they are not incorrect in suggesting that causality goes from spending to taxes, like it goes from investment to savings. It's implicit in the Keynesian/Kaleckian model in which autonomous spending (government spending is in there) determines income through a multiplier process. And taxes, like savings, grow with income. But it is important to note that politically (again this is not analytically, but politically) countries that went for a more ample Welfare State opted to tax their citizens, particularly their more wealthy citizens, at a higher rate. Tax increases on the wealthy should be (and are) part of the progressive agenda. It has an important distributive effect, and it makes the spending politically acceptable. At this juncture, however, even Blanchard says that we should just borrow, since interest rates are low, and will remain low.

The crucial point is that overall MMTers have been helpful in moving the Dems in the right direction (the right direction is to the left), and that is a good thing. The problem with Dems is not the existence of a few social democrats or socialists in their midst. In fact, even being generous there will probably be just three democratic socialists in the presidential primaries (Bernie, and, perhaps, Warren and Tulsi). The problem is the vast majority of neoliberals that still dominate the party. The same could be said about MMT. The problem is not the exaggerated propositions of MMTers, but the excessive fear of inflation when there are too many relevant problems to be concerned with.

Friday, March 8, 2019

Keynesian Economics: Back from the Dead

The Godley-Tobin Lecture by Bob Rowthorn, to be published by the Review of Keynesian Economics.

Rowthorn suggests that many Keynesian features are part of the mainstream now, in particular showing a stable Phillips Curve without a natural rate. I remain more skeptical about the return of Keynesianism within the mainstream, but worth listening to his thoughts.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)