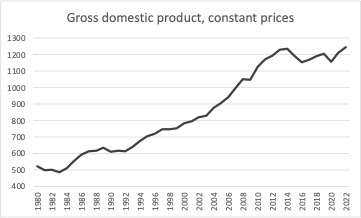

It's been a while since I wrote about the Brazilian crisis (a summary of the previous catastrophic election here). In part that election and the continued crisis explains why I have written less, not just about Brazil. This has been a long economic depression that started in 2015 (see graph), with a coup in 2016 and since 2018 the added problem of a right-wing authoritarian regime that won an election that was only possible with the political proscription of Lula. But at least the political problems have started to be solved with this election.

Source: IMF. Peak in 2014 (2022 estimated)

The Lula election last Sunday is a redemption story, no doubt. Not only because there was no prove of his corruption, even if corruption existed,* and even though the international press, including the reputable media continues to refer to him as an ex-convict. Corruption is a problem, but the one that matters is associated to the needs of governance in Congress, and the current Bolsonaro government has dealt with payments to members of congress through the so-called secret budget. And that will not vanish, and that could cause problems in the future. But in all fairness, the size of that and the implications in terms of the functioning of the political system, let alone for economic growth or the well-being of the population are far from clear.

At any rate, that is a secondary issue. The problems that Lula and his coalition will face are on the economic front. And not because Brazil is facing a serious crisis, like neighboring Argentina. This is the worst economic crisis in Brazilian history, but is purely political, and has been aggravated by the decisions taken by the Brazilian authorities, starting in 2015 with Dilma, trying to stave off the coup, and then with Temer and Bolsonaro.

The main problem is the limit on government spending, the ceiling that would limit the ability of the government to promote not just a more solid recovery, but more importantly one that allows for increasing real wages for those at the bottom. Fiscal rules were put in place for this reason, for the possibility of a left of center government, and that is why financial markets were convulsed by Lula's talk this week, and the real devalued. Not that it matters much.

There will be some arrangement that will allow the expansion of spending to cover the social transfers, and some additional social spending that was left out of Bolsonaro's last budget. But fiscal conservatism will be something that will have to be combated throughout the next four years, and not just from the opposition. Many within the government's complex coalition will be for austerity. There will be plenty of time to talk about that, and I would normally be pessimistic.

However, two things make me a bit optimistic (which is not very characteristic). It is important to differentiate what Lula does from what he says, or even what he believes. This is true of many on the left in Latin America. Before the previous Pink Tide, two decades ago, I was more concerned with the pleas for fiscal responsibility of many on the left. As it turns out, many of the progressive governments did expand social spending, and promoted an acceleration of growth, including Lula, and a significant expansion of real wages. Someone will say, this is not 2003, and there is no commodity boom that will lead to growth, or at least the easing of the external constraint.

However that was not what explained the Brazilian growth in the first Lula government. The external constraint was eliminated to some extent by the boom in commodity prices, but the fundamental source of foreign reserves was financial, and resulted from the relatively high remuneration for assets in domestic currency. That was to some extent possible because interest rates in advanced economies have been low in the center, and they will likely remain low (even if they are increasing right now). So on that front it is possible to expect an acceleration of government spending, and higher transfers to the relatively poor, with higher real wages at the bottom. Besides, Bolsonaro is gone, and that should be reason enough to be optimistic about the future.

* There is no evidence of Lula's personal corruption. The infamous Triplex apartment, for example, is clearly not his, and he never benefited in any other proven way. Many Latin American politicians, including Eduardo Cunha, which was instrumental in Dilma Roussef's impeachment, does appear in the Panama Papers. Paulo Maluf had undeclared accounts in Switzerland, just to name another Brazilian politician for whom there is objective, material evidence of corruption. To suggest that Lula knew about corruption, is more or less like saying that FHC knew about the buying of votes in congress to allow for his reelection (or many other issues during his government). In other words, is to say the obvious.